Rare Earth: Is China evil?

16 11 19 14:57

Part 1: The perceived Risk

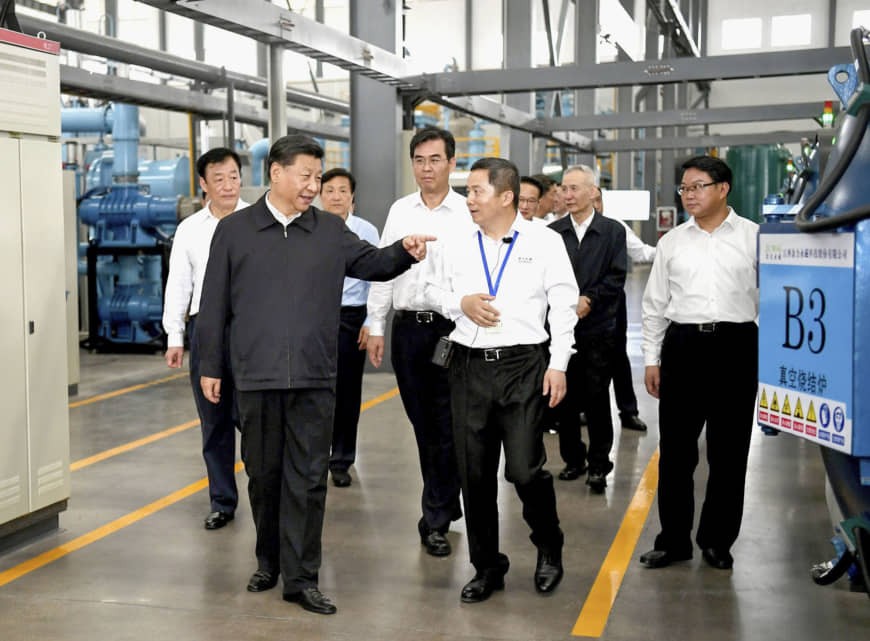

The geopolitical risk arising from rare earths is a perceived one, sometimes at both ends of the spectrum as we have seen in May 2018, when General Party Secretary Xi Jin Ping visited the Chinese company JL Mag together with his top trade negotiator, Vice Premier Liu He.

The media, including China's, fell over themselves to report a rare earths boycott threat from China, linked to the trade war. Even 2 China ministries briefly fell for the media hype, apparently before talking to their in-house experts.

Missing the Point

In our humble opinion, the point of this visit had been missed.

JL Mag are a permanent magnet manufacturer, they BUY rare earths to make magnets, they don't sell rare earths. Permanent magnets are at the core of crucial current and future technologies.

JL Mag's location is at the starting point of the Red Army's famed Long March, a torturous undertaking during China's civil war to evade an enemy of superior strength.

These two elements were the base of a symbolic point Xi intended to make: “We are now embarking on a new Long March, and we must start all over again!”, he said during the visit.

If there was any threat intended, then it was to cut off the US from China's permanent magnet supply, world market share China ~75%, Japan ~17%.

Permanent magnets are the real vulnerability of the US, not rare earths.

Besides, we can't recall a recent province tour of Xi Jin Ping without Liu He having been around.

Part 2: The Rare Earth Commercials

The commercials of rare earths elements are really, really difficult.

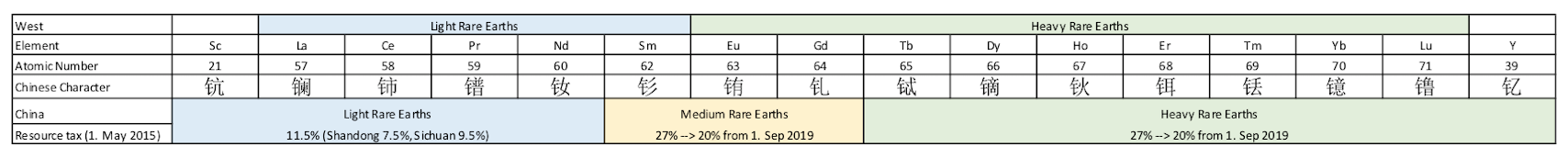

Rare earths are 17 elements, of which 2 are not really rare earths and one more doesn't exist in nature.

So, we are talking of 14 elements. You can't mine them separately, they all stick together in the same ores like monazite, bastnaesite, xenotime or eudialyte, just to name a few.

In terms of commercials, broadly speaking - exceptions apply, you either produce them all or you produce none. At different times different elements were hot-sellers, depending where application technology demand was headed. Example: Europium for now obsolete colour tv and computer CRT monitors used to be a hot-seller and cost more than US$ 300/kg, now it costs around US$ 30/kg.

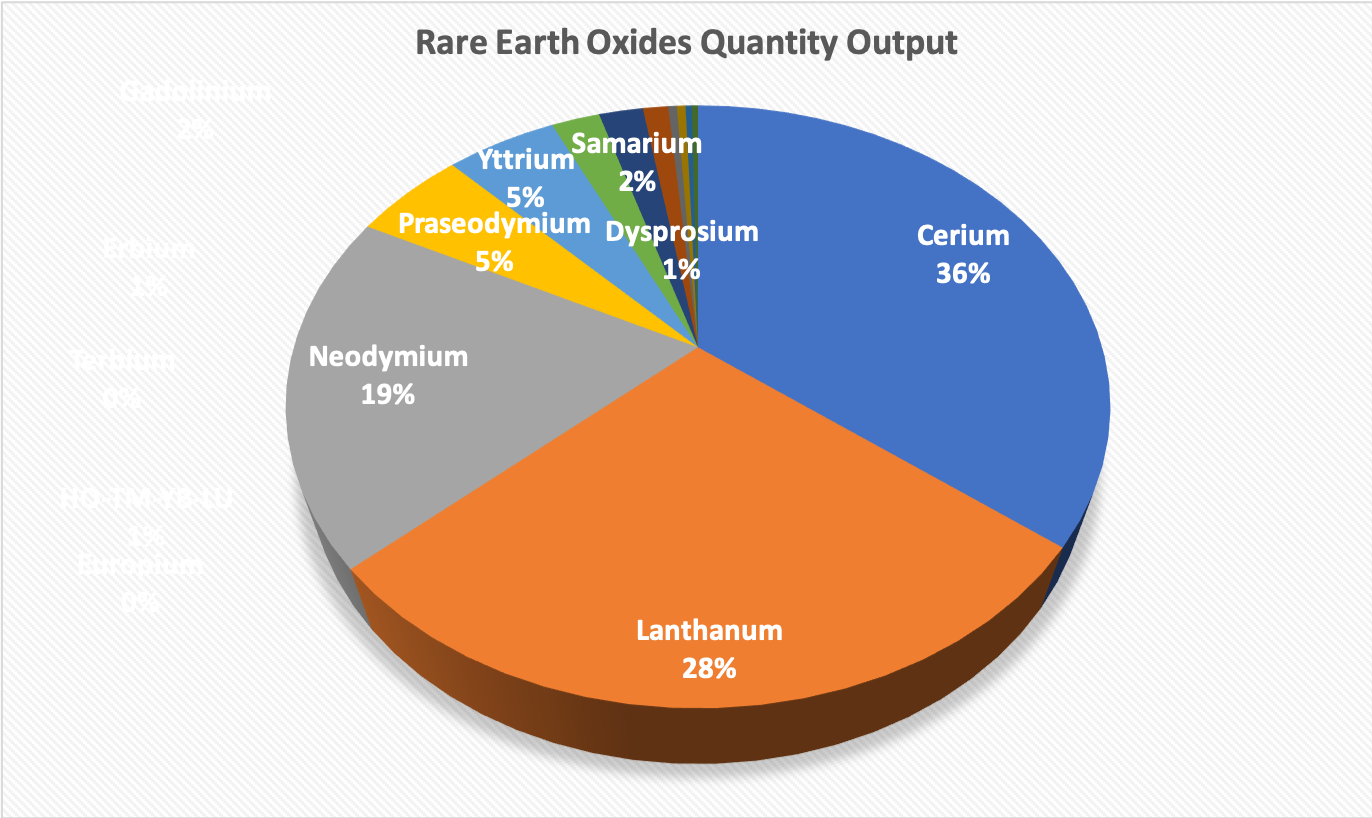

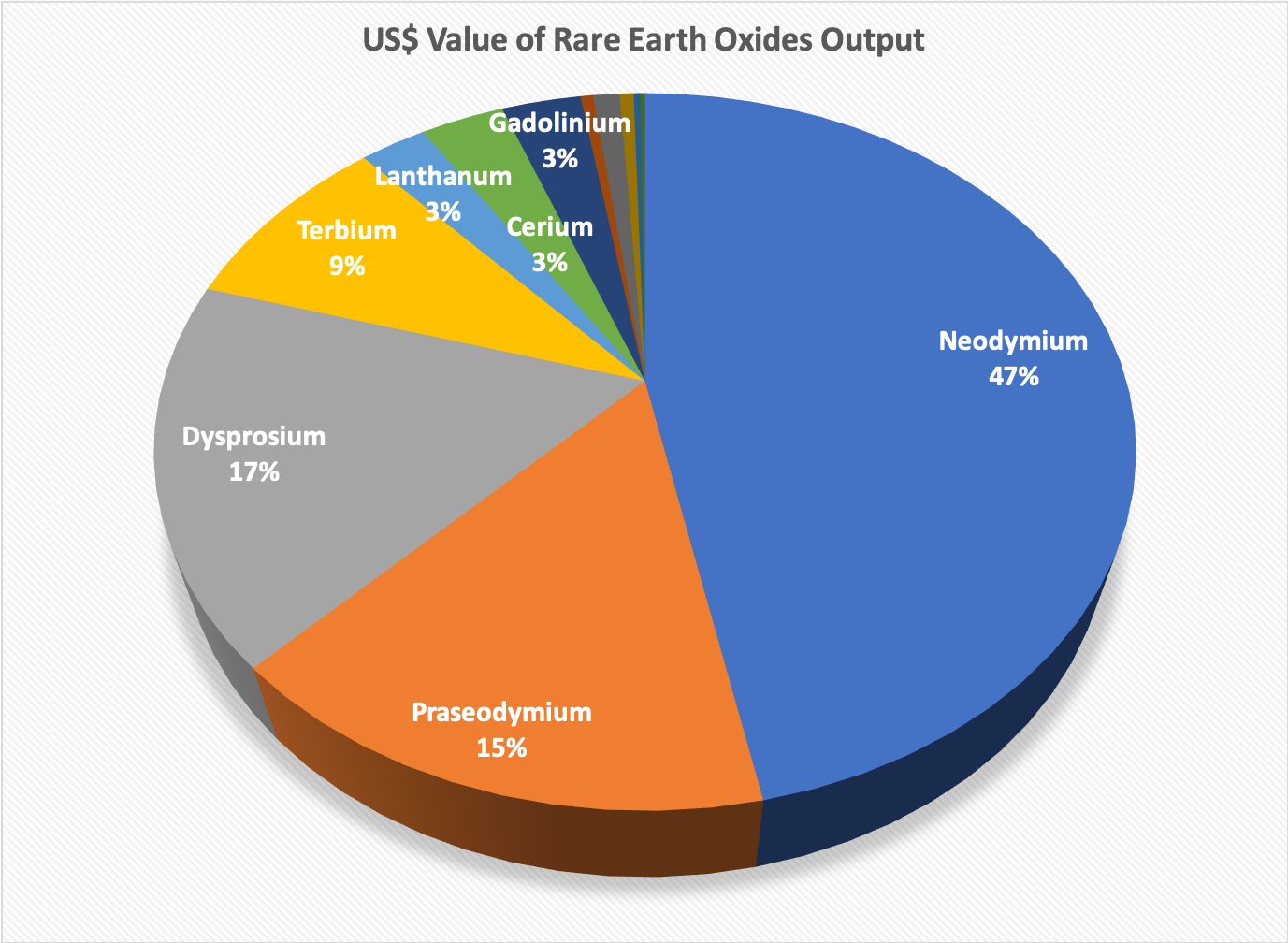

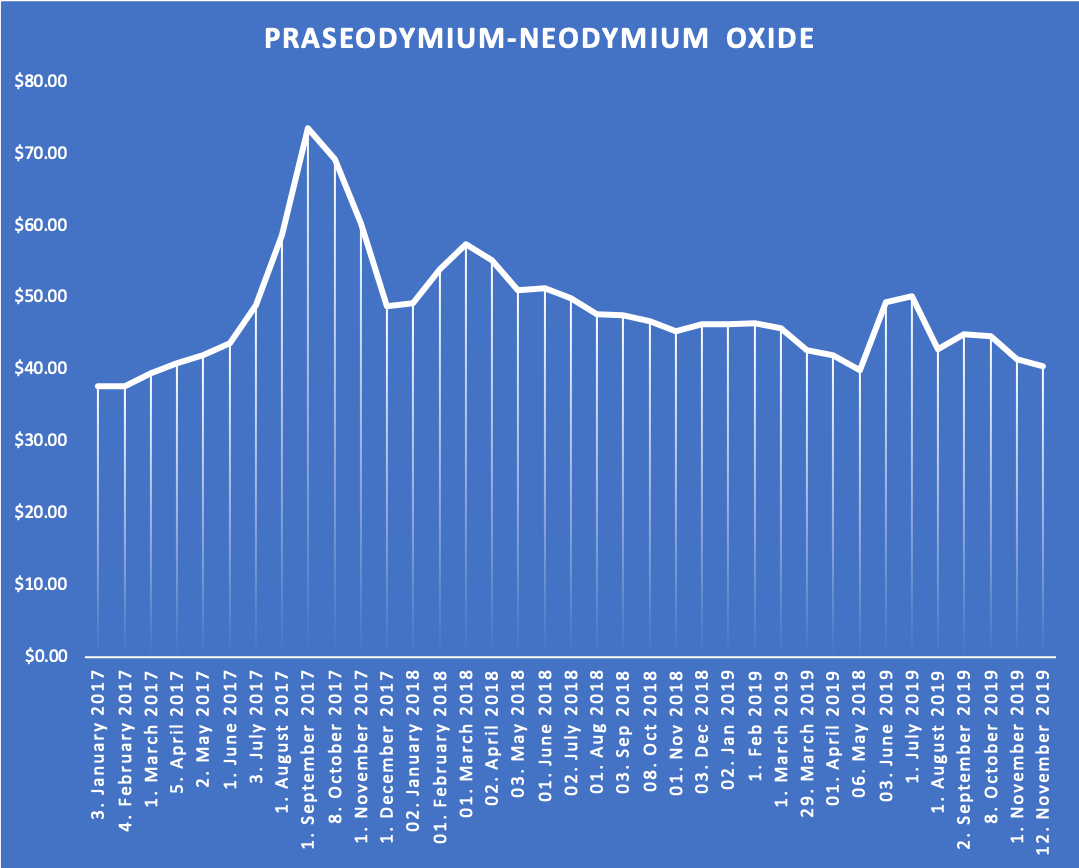

Currently, permanent magnets are hot items and the related 4 rare earth elements constitute 88% of the value of all rare earth oxides. Broadly speaking, in order to get enough supply of these 4, you overproduce all others.

Even worse, the rare earth elements are not contained in the ores in equal proportions, so the quantities of each rare earth element in the rock are hugely disproportionate to what can be sold.

Therefore, the world output of some rare earth elements is >1.5 times world demand.

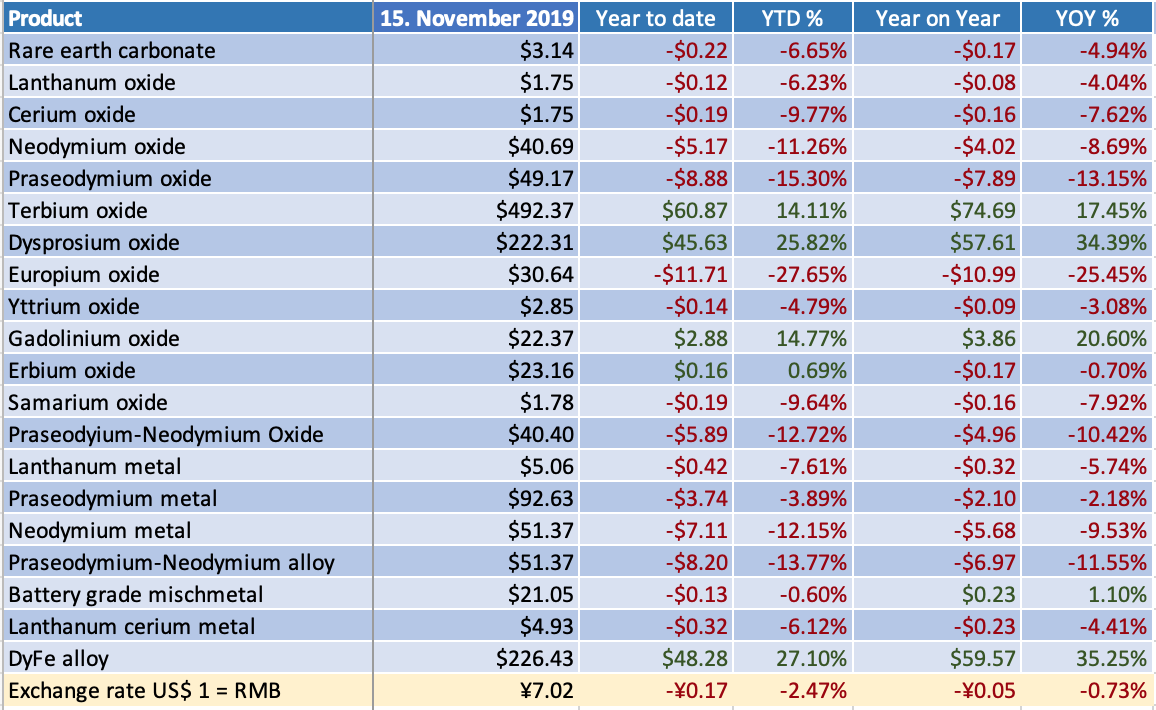

Consequently, you have some rare earth elements that sell at below US$ 2/kg, while others sell at up to US$ 500/kg.

Note that China pours most of its rare earth research funds into application research of those rare earth elements that are oversupplied and "as cheap as cabbage".

The market and the pricing or rare earths evolves around very fickle supply and demand balances and this is not a large volume commodity market. Therefore, the government interferes in rare earths prices from time to time, for example by setting production quotas and by playing with the resource tax.

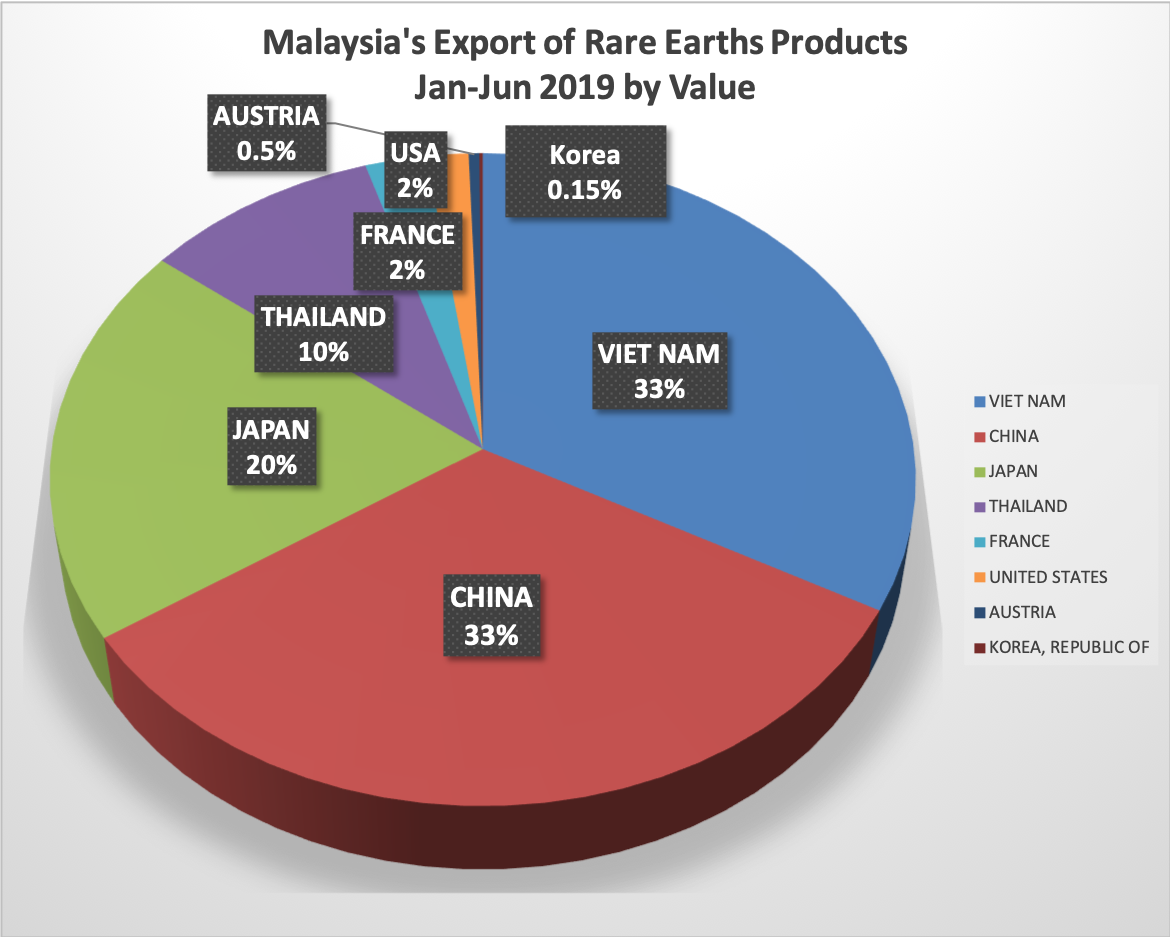

There is currently only one non-China entity turning out the tradable form of rare earths elements, rare earths oxides, which is Japan-financed Lynas.

The increasing supply of rare earths oxides from Lynas has dampened prices for those products Lynas supplies, whereas prices for some rare earth oxide that Lynas can't yet supply have soared.

China is not only 80% of rare earths output, it is also <60% of rare earths consumption.

No junior miner out there can make it off the ground and not sell to China, there is simply no big enough market elsewhere, or even no market at all.

Even Lynas sell a significant part of their Malaysia factory output to China and Chinese enterprises in other locations.

At the same time, the notion contained in many junior miners feasibility studies that prices will rise as they enter the market is ill-conceived, to put it rather mildly.

Part 3: China's situation - the EU-China meeting

Some years ago we had the privilege of sitting in a regular meeting of the EU Commission Raw Materials Group and the Chinese Ministry of Industry & Information Technology, which gave us the opportunity to begin to understand how enormous the task on the Chinese side was.

The ill-considered non-tariff trade action of China against Japan, which by the way was not limited to rare earths, had caused a massive rare earth price spike.

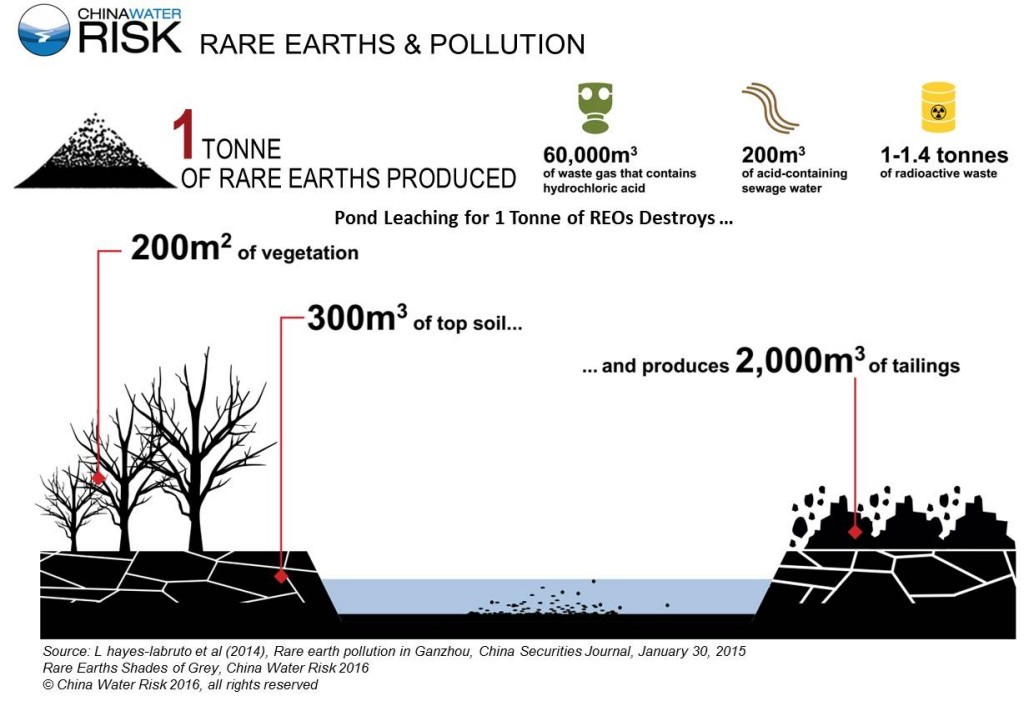

Uncounted companies in China began rogue mining and separation of rare earths in order to profit from the subsequent rare earth craze, to massive detriment of the already challenged environment and to public health. Plus - even more importantly - polluting already scarce water supplies.

At night trucks would even steal rare earths from the mines and carry it to some villages for downstream processing under appalling conditions.

The produced goods would be misrepresented upon export. Brownish, yellowish, reddish or blueish powder can be anything under the sun, so also China Customs could not control it.

The initial measures taken were floodlight at night, fences and camera surveillance of rare earths deposits.

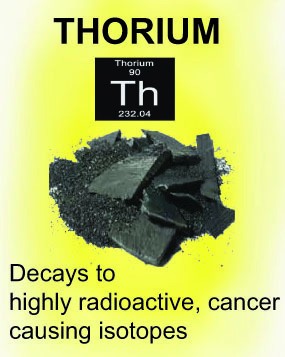

In terms of pollution, we are not talking only ammonia, sulphuric acid, HCL plus other tailings. Rare earth elements love radioactivity, mostly but not exclusively thorium. Haphazard disposal of radioactive waste from rare earth operations has created mountainous long term problems.

Even somewhat legal enterprises and state-owned companies where playing the several ministries in charge in Beijing, plus local party officials, whose career at that time depended almost entirely on economic development of their region.

The ministry made 2 important announcements during the Raw Material Group meeting:

- The Chinese rare earth industry will be concentrated in 6 large state owned enterprises.

- In view of the a.m., China principally will only produce for its own demand, but will consider supplying the EU for clearly defined demand of defined products.

- Herein we can see one of the first examples of environmental and public health concerns overriding commerce in China.

Part 4: China's Rare Earths Policy

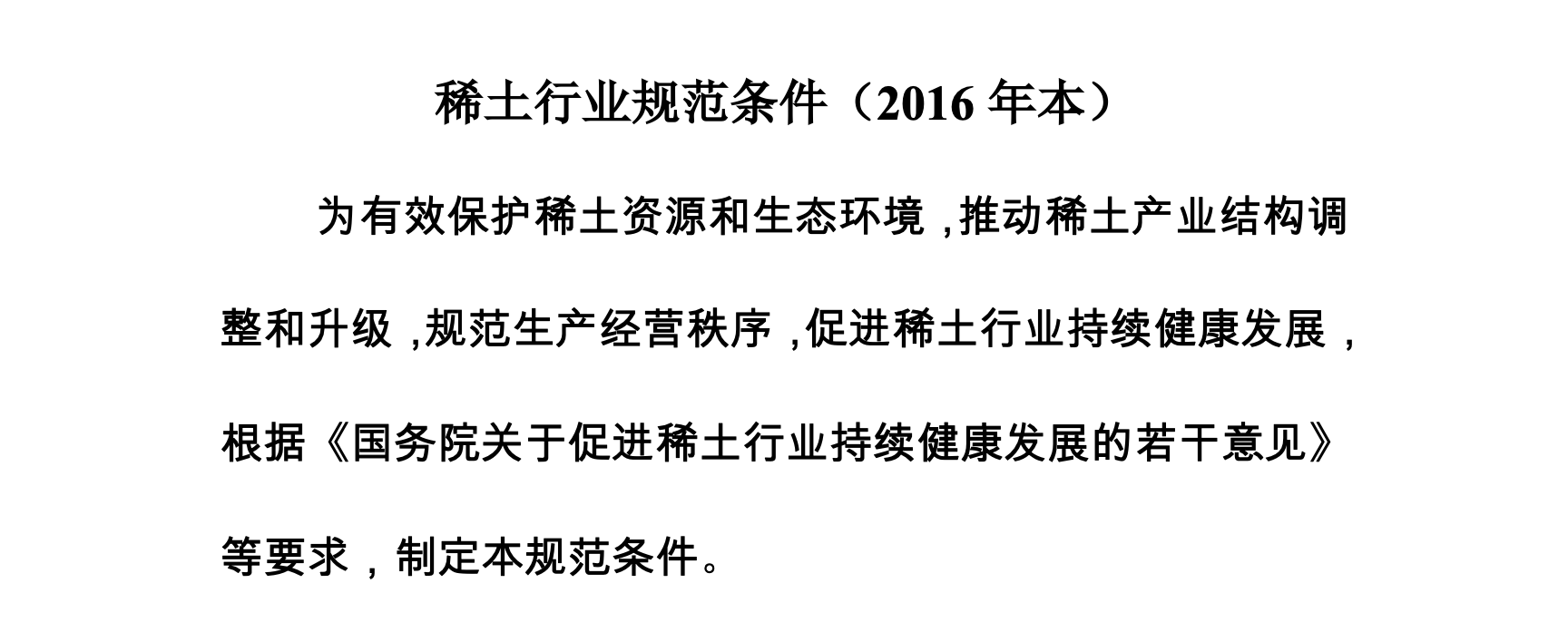

China needed 2 years after this meeting to come up with a comprehensive rare earths policy, that is relentlessly being driven by a combination of ministries on national, provincial and local levels.

As old China-hands know, regulation in China is always ambiguous and ambivalent, to allow room to maneuvre or even backpedal, but this particular policy contained definite key performance indicators.

The direction this policy takes is reducing use of domestic resources, thereby mitigating not only the environmental issue, but also to create long term sustainability, as China itself has a vastly lower assessment of its own rare earth resources than the US Geological Survey (USGS) assesses.

Most western analysts blissfully ignore this gap.

We would be tempted to argue, that the Chinese know their own resources better than the USGS.

China's New Era: The Age of Compliance

No longer is economic success the sole career denominator for China's local officials, compliance with laws and regulations under their rule as well as ideological faith rank higher, which means national policy does not evaporate at Beijing city limits anymore.

Some key performance indicators set by the central government are being reached, but still the conditions are not satisfactory, as there are no limits to creativity in China when it comes to evading government controls and skipping the rules.

Current examples are imports of rare earths from Myanmar, that are much larger than Myanmar could possibly ever provide, recycling and production by subsidised "comprehensive resource utilisation enterprises", which all increased the supply of undocumented rare earths circulating, thereby putting pressure on prices. Add to that imports of raw material, misrepresented, that are processed to rare earths oxides using existing idle capacity of otherwise compliant rare earths companies.

And this is not only private enterprise. Cutting through the layers of investments in Baotou's rare earth companies you will eventually end up finding either local, provincial or national state funds being the actual controllers.

The managers of China's rare earth companies have two hearts beating in their breast, one for the company and one as the party officials of varying ranks that they mostly are. That could be a contradiction, but socialism is supposed to thrive on contradiction, according to a former party chairman.

The chairman of Baotou Rare Earth Group, China's largest rare earth company, announced at the 15th International Rare Earth Conference in Hong Kong last year that China will not repeat the "disastrous mistake" of 2010.

This, as far as I know, was the first public, official admission of China having caused the rare earth crisis by non-tariff trade action, something the government had always denied so far.

Part 5: Does China trade fairly?

China likes to portray itself as harbinger of free trade and globalisation.

Fundamentally, China is a nation built on exports, just like Japan, Korea and Taiwan are. China's concept basically follows these blueprints, but with a significant twist.

In order to give Chinese export manufacturing industries access to the worlds lowest priced raw materials, domestic overcapacity of raw materials is basically built into the system (believe it or not, also in rare earths China has overcapacity). This to ensure oversupply and subsequent price pressure.

However, in a free trade environment, domestic and international raw material prices will equalise through trade. Not so in China.

In order to prevent equalisation of price levels domestic-international from happening, China uses its VAT system, introduced in 1994.

VAT as such is cost neutral. Domestically a company pays VAT included in the prices of its production consumables and it charges VAT included in its sales price of its finished products to its customers, and the difference of paid VAT and charged VAT is remitted to the tax office.

Typically, in a regular economy like the EU, once a product is being exported, the exporter is being refunded 100% of the VAT paid.

That is not the case in China.

China discriminates among its export products. In general one can say, products of low added value such as raw materials have a low VAT refund upon export, whereas products of high added value get a high VAT refund upon export.

China's current VAT rate is 13% (some exceptions apply here and there).

Metaphorically speaking, a Chinese refrigerator exporter will receive 13% of VAT refund upon export, a Chinese pig iron exporter will receive zero VAT refund upon export.

For China's rare earth there is zero VAT refund upon export.

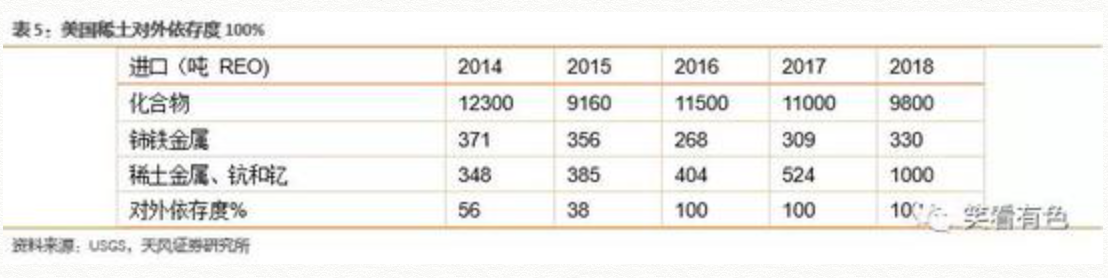

In regular commodities, such regime would render export prices with no refund of domestic VAT internationally uncompetitive. But in rare earths there is simply no other choice, importers have to buy from China and end up with 13% higher rare earths cost than China domestic rare earth buyers, because there is no VAT refund upon export for rare earths from China.

China has been using this 13% cost differential trying to attract US catalyst companies such as Albemarle, WR Grace, BASF, etc, the volume-wise overwhelmingly largest importers of Chinese rare earths in the US, to move their catalyst production to China.

Of the 9,800 tons of rare earths oxide China exported to USA in 2018, 7,300 tons were cerium and lanthanum, mostly for catalyst use. If the US would not buy them for the one or the other reason, there would be no alternative market for these 7,300 t.

So is it fair trade or not?

China dominates the world market (i.e. >15% of world output) in all but a handful of nonferrous metals and is a dominant exporter of these, including rare earths.

China reviews and adjusts its VAT refund upon export once, in exceptional cases twice a year, mostly in order to interfere in trade volumes, either way. That is trade manipulation.

So, the answer must be no. China does not trade fairly. QED.

Part 6: The opportunity for junior rare earth miners

As mentioned above, Chinese rare earth policy encourages imports of rare earth raw materials.

The import duty is zero, only VAT is payable upon import to China.

In case of rare earth carbonate or concentrate, the China domestic resource tax levied on domestically produced rare earth concentrates does not apply to imported product, which actually gives imports an edge over China domestic produced concentrate.

Typically, a junior miner will require US$ 1 billion capex for creating the entire value chain from ore to oxide, impossible to get, whereas ore to concentrate or carbonate requires only US$ 100-200 million capex.

Therefore the default strategy of junior rare earth miners is to turn out a concentrate and sell it to China.

But what if the rest of the world wants home-made rare earths oxides?

There are about 60 rare earths deposits worldwide outside China, that junior miners try to develop.

The entire world market of rare earths oxides is around US$ 3.5 bio per year, >60% of which is China domestic.

No investor in its right mind will put up US$ 1 bio investment for an ore to oxide operation with no cash flow to be expected for >4 years, and then face aforementioned competitive conditions.

The answer to out of China rare earths oxide production is environmentally benign recycling.

As described above, China produces 75% of the world's rare earths magnets. These magnets are being exported and they are core parts of - for example - wind power, electric vehicles, and even include the dozens of electric motors in conventional combustion engine cars, to name just a few applications.

The end of life scrap from these magnets can be used for recycling. This "NdFeB" magnet scrap contains the 4 elements that are 88% of the total value of all rare earth oxides today.

While there are already a couple of rare earth recycling enterprises in China with large capacities, albeit not environmentally benign, there is only one commercial magnet recycling company in the rest of the world with a competitive, environmentally benign concept.

That company is Geomega in Canada.

From all the rare earth companies we know, this is the only one who has a chance to turn out rare earths oxides in North America from 2020/21.

So, in Rare Earths, are we safe?

Fundamentally, in rare earths China does not behave differently from a regular monopoly.

In terms of commerce, I am rather confident that the commercial managers in China's rare earth space act in good faith, even if in a largely state-owned and therefore political environment.

The Chinese Association of Rare Earth Industry, however, announced related to the short-lived rare earth boycott hype, that it would follow the orders of the party, as if this was not anyway self-understood. There was no point in making such statement, other than stirring up concerns.

The National Development & Reform Commission as well as the Ministry of Commerce also publicly pondered a rare earth boycott, not helpful either.

And all that amplified by Global Times editor Hu Xijin, who is always at hand when it comes to making belligerent statements.

Professor John Mearsheimer says: Politics trump economics.

And that is, what we are seeing currently.